This article was written by Zack Scott, Transformational CIO and Lean Evangelist with more than 20 years successfully driving Agile transformations in start-ups, SMEs as well as in corporate organisations from the bottom up as technical leader and architect as well as from top down as senior manager and executive in Europe and Australia.

In this series, Zack will look at the evolution of organisational matrix structures and propose a 3rd dimension to create '3D Lean' - a powerful model to support your Agile Lean Transformation.

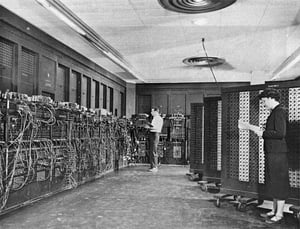

Over a generation ago - most of us will know it only from stories and studies - computers were huge electronic monsters only affordable by governments and big organisations. People who worked with those behemoths were highly specialised engineers - often not to be understood by non-engineers. Results of both technical and cultural constraints were an application architecture that was monolithic in nature as well as organisational structures that were extremely siloed.

Solutions were clunky. When something broke, whole systems became unavailable and it took several experts often a long time to locate and fix the problem.

Solutions were clunky. When something broke, whole systems became unavailable and it took several experts often a long time to locate and fix the problem.

Then, in the late 1960s, Larry Constantine came along and started to talk about coupling and cohesion. In theory, this could reduce the complexity of those behemoths, lowering defect rates whilst improving their reliability. If something broke, it would result in only partial system failures.

However, machines were still very expensive and not sophisticated enough to cope with the complexities of the systems both intrinsic and imposed by solution designs. Engineers were still specialists who worked in different teams and locations. Thus, monoliths and silos survived and continued to thrive in order to satisfy the growing needs of system performance and solutions delivery.

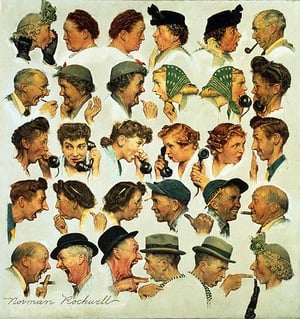

Not too long ago now - and many of us will still remember - software engineering divisions were split into groups of specialists (developers, testers, ops), which often worked in different locations - rooms, buildings, continents - sometimes in different companies even. Contact with the rest of the organisation was being kept to a bare minimum of handing over requirements - or complaints - through well-defined "channels" of special non-engineering roles filled by those few who dared to talk to the engineers.

Delivering any such requirement could often result in long-winded iterations - or delivery ping-pongs at hand-over points between two engineering groups, e.g. "development" and "test" where, not unlike Chinese whispers, the initial message was (mis-)understood and forwarded slightly altered, resulting in a solution that was so much different than the intent of the initial requirement. Provided with some clarifications from UAT, the whole cycle was repeated again with equally questionable outcomes.

Delivering any such requirement could often result in long-winded iterations - or delivery ping-pongs at hand-over points between two engineering groups, e.g. "development" and "test" where, not unlike Chinese whispers, the initial message was (mis-)understood and forwarded slightly altered, resulting in a solution that was so much different than the intent of the initial requirement. Provided with some clarifications from UAT, the whole cycle was repeated again with equally questionable outcomes.

Fast forward to the new millennium, in an attempt to improve the quality of a solution as well as its delivery time by reducing the number of hand-offs, many engineering groups started to work in cross-functional, co-located teams - quite a revolutionary idea after generations of specialised isolation!

Furthermore, after years of working together with engineers those members of an organisation who 'handed over' business requirements to engineering teams had learnt two important lessons:

As a response to these lessons learnt, software delivery groups began to embed customer representatives as "Product Owners" into their teams to enrich their cross-functional groups.

As a response to these lessons learnt, software delivery groups began to embed customer representatives as "Product Owners" into their teams to enrich their cross-functional groups.

The first squads were born!

Stay tuned for the next article of this series!

The next article of this series will be based on Constantine’s and Conway’s fundamental guidance to effectively and sustainably scale squads and tribes in organisational alignment.

These Stories on CIONET Australia

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think